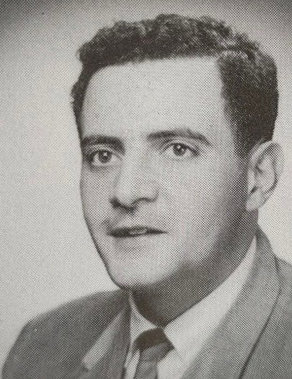

Coach Andrew Scerbo made Major League dreams come true

His teachings were gospel, now they’re eternal

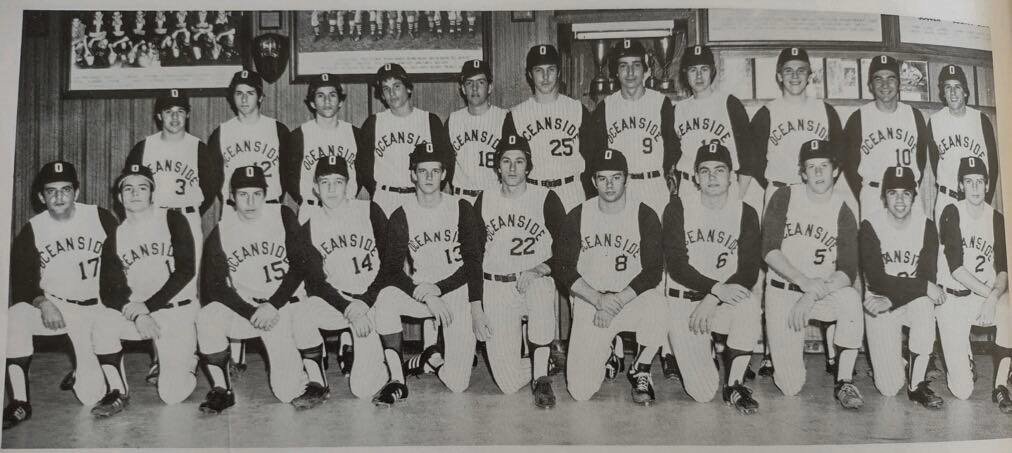

Andrew Scerbo, Oceanside High School’s baseball coach for 32 years, was among the winningest coaches in Nassau County history, winning 12 league titles and finishing with 454 wins. His 1988 team was ranked among the top 10 in the country by USA Today.

Scerbo died March 6, at age 86, surrounded by loved ones at his home in Delray Beach, Florida.

“Andy didn’t die, he lived ... with class, grace, dignity and laughter, and he shared that life with all of us,” Andy Morris — who was at Scerbo’s side for many of his coaching years —said at his funeral service.

Many students Scerbo coached became professionals, and three of them — Dennis Leonard, John Frascatore and John Costello — made it to the major leagues.

Writing on Scerbo’s online tribute wall, Costello described him as an inspiration to hundreds of young athletes and thanked him for helping him make his childhood dream come true.

“You not only taught us the proper way to play the game of baseball but you taught us how to be young men,” Costello wrote. “I still remember you (in) 1979 introducing me to Dennis Leonard who pitched for Whitey Herzog with the Royals. At the time I was very impressed by meeting him. I eventually made it to the Major Leagues and also, ironically, ended up pitching for Whitey Herzog with the St. Louis Cardinals.”

Costello also shared one of his favorite memories, of invited Scerbo to Shea Stadium to watch him pitch against the Mets.

Born in Brooklyn, Scerbo grew up in Bellmore, where he attended Mepham High School. He played football, basketball and baseball, but he fell in love with the art of baseball. After high school, he turned down a contract to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers organization and attended Ithaca College on a baseball scholarship. While there he played in the College World Series, and his success led him to be drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals.

He once confided in another coach and friend at Oceanside High School, Richard Woods, that his competition to make the big club was Dal Maxvil. They both made it to the Cardinals’ spring training camp in the early 1960s, when Maxvil started his career. Woods recalled, “Scerbo told me, ‘We both could field, we both were not great hitters, but Maxvil was a little better hitter than I was.’”

Woods recalled fond memories of Scerbo both as coach and colleague.“As my high school coach, he selected me as his captain, an honor I won’t forget,” Woods said. “As his colleague he taught me so much about our profession, mostly in the affective areas. ‘You’re a teacher first, Woody!’ were words that always rang in my ears during many school situations. He taught by example in the way he guided and cared for all who needed him. He exuded love just by his nature.”

Since he didn’t make it to the major leagues, Scerbo put his energy into coaching and in 1963, he was hired at Oceanside High School as a physical education teacher and coach. His teams were known for always being well-prepared, knowledgeable and confident. Errors, he used to say, were part of the game — but not knowing how to execute the play was an error you should never make.

Michael Zimmerman, from the class of 1973, made the varsity team in Oceanside in 1971 and was the captain two years later. He went on to coach because of Scerbo, having seen the positive effect coaching could have. He taught in Florida and California for 28 years, “due strictly to the fact of his influence,” he said.

“He taught us what character was about,” Zimmerman said, “integrity, all the positive traits that you could want to pass on to students.”

Zimmerman remembers a time when Scerbo left him out of the lineup. Confused, he asked him why. “Slowly and surely,” he said, “he sat me down and explained, ‘hey, you know what, last game there was a ball hitting the gap and you didn’t hustle after it, and therefore you didn’t deserve the privilege to play.’ Well, you talk about a lesson learned. We never had that issue again.”

Scerbo taught tough love, but that didn’t stop him from being a positive influence and second father to some in a time of civic unrest in America, as the nation delt with the anti-war movement, Vietnam, Watergate, and ongoing protests for rights. “We needed other mentors and other role models, and he certainly was that,” Zimmerman said.

Players saw Scerbo as a surrogate father. At times, if things went awry in a game, rather than get upset, he’d turn his hat sideways, cross his eyes and stick his tongue out in a whattaya-gonna-do fashion.

During a non-league game at Seaford High School against opposing coach Vinnie Conlon — his good friend and best man at his wedding — he argued a call, got thrown out of the game and proceeded to sit in Conlon’s dugout and put on a Seaford baseball jacket.

One of his football players, Craig Jacoby, remembered making the high school squad as a 10th-grader.

Typically, because he was a rookie, everybody was calling Jacoby by the wrong last name. He said to coach Scerbo, “My name is Jacoby.” Scerbo responded, “When I see you block someone, I’ll call you by the right name!” The next season, after a tremendous amount of off-season work, he complimented a beaming Jacoby, “Welcome back, Jacoby!”

Baseball was Scerbo’s passion, but his family meant everything to him. Regina, his wife of 40 years, was said to sincerely complete him, and they filled their marriage with travel, golf, sunshine and retirement together, but mostly with love.

Scerbo was a devoted and loving father to his son Daniel, who predeceased him, and was a devoted grandfather to Sean, Andrew and Ryan. His grandsons spoke lovingly of Scerbo at his memorial service, as did his daughter-in-law, Cathleen, who used words and poetry to convey their love and remembrances.